In Guwahati, Assam, on February 14, 2026, Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched the Kumar Bhaskar Varma Setu. The six‑lane bridge over the Brahmaputra River was hailed as a landmark project, constructed at a price of about ₹3,030 crore. It is projected to reduce time to travel from Guwahati to North Guwahati from nearly 50 minutes to around 7–10 minutes thereby enhancing connectivity, trade, and access to the Kamakhya Temple. But when it was opened – only 24 hours after the crossing – the bridge was in tatters with gutkha-spitting stains, and a mass protest erupted.

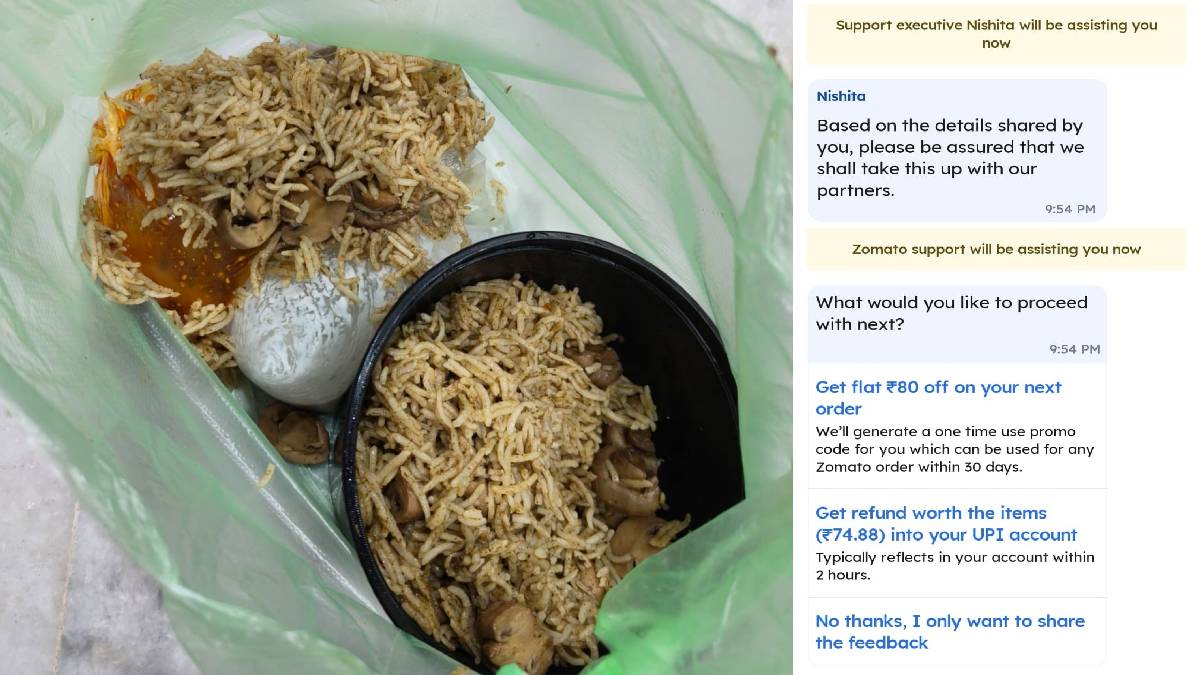

Neighbors said they noticed red stains on gutkha’s spit across the bridge’s walls and pathways. To some, this was a matter of cleanliness rather than filth but it was also a statement of civic responsibility. The disappointment was heightened because the bridge had been inaugurated a day before, so the stains were a harsh reminder of bad habits among the masses undermining large infrastructure projects.

On social media, citizens vented frustration over the stains; they used pictures and videos of them to express frustration. With that in mind many wondered why this kind of behavior keeps going unregulated, and why no harsher penalties are in place. The episode reignited demands for a nationwide ban on gutkha, which is not only harmful to health but causes the degeneration of public infrastructure. They said if new pieces of infrastructure are not kept up and respected, then they are not worth thousands of crores of money at all.

Carcinogenic product Gutkha is commonly known as a carcinogen that is associated with oral cancer and other serious conditions. Its circulation and consumption have never been reduced despite prohibitions in some states. Aside from being negative for health, gutkha spitting promotes unsanitary circumstances and infects people and defiles the image of places once they are used to living. The stains on the Kumar Bhaskar Varma Setu are only one example of how this habit compromises public health and national hygiene messaging.

The incident has led to discussion about why the central government was reluctant to impose a national ban on gutkha. Some states have restrictions, but enforcement varies; loopholes persist to help sales take hold. Without a coherent policy, critics say both health and infrastructure will still be harmed. Proponents of a ban say it would lead to reductions in consumption and increases in cleanliness and preserve public investments in infrastructure.

These gutkha stains on newly inaugurated Kumar Bhaskar Varma Setu reflect a more general question on duty-giving, policy, and good government. Infrastructure projects are meant to uplift communities, but rather when they become embedded in public habits and weak enforcement, their value diminishes. For some, this incident was a wake-up call: India urgently requires stronger action against gutkha, in terms of both the health of its people and the cleanliness of its cities.