One of the holiest rivers in India, the Ganga River. It is worshipped by millions of people every day, who believe that it reflects purity, life, and spiritual connection. Ceremonies such as the Ganga Aarti draw tens of thousands of devotees to the riverbanks, who are there to pray, light lamps, and sing hymns. But the river that is worshipped at night, the same river commonly faces pollution the very next morning. Waste from ceremonial garbage, plastic, and whatnot, is flushed directly into the water, making something that serves as a symbol of holiness a garbage dump. This paradox begs the big question: how are we able to honor the Ganga and still pollute it?

Pollution continues to be a problem despite innumerable efforts to clean the Ganga. Following religious rituals, waste is often tossed instead of being collected to go away in good faith, being dumped and the resulting garbage washed into the river. Plastic bags, flowers, food remains, and other trash float downstream that endangers aquatic life and poisons the water. Such practices not only harm the Earth, but damage the same faith that awakens worship. Some pray for purity and blessings, but the deeds which they undertake are tainted and destructive. The contradiction is striking: worship during the night, pollution in the morning.

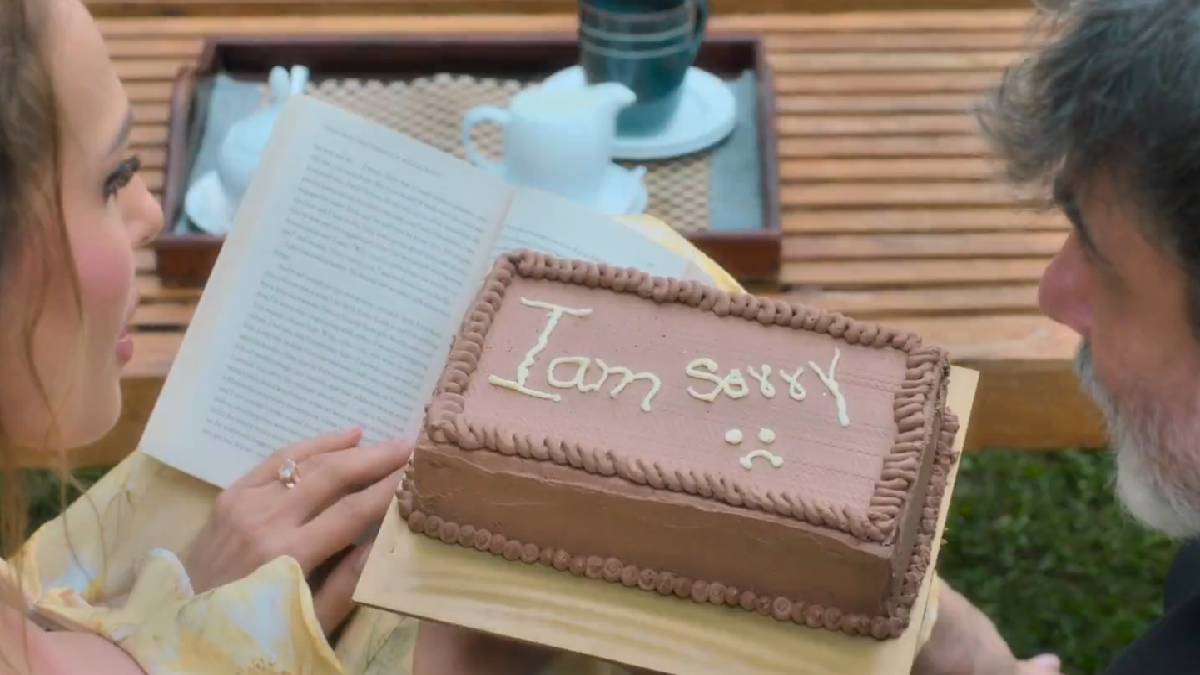

We worship Ganga at night & pollute it in the morning.

— Tarun Gautam (@TARUNspeakss) February 6, 2026

Instead of collecting garbage after Ganga Aarti, they are literally flushing it in Ganga itself.

Ganga is never going to get cleaned if this continues....

Video by SaneemaWala pic.twitter.com/7mXb8b5TUY

For those facing this continuing pollution, the reasons are complicated. Most people do not realize how much long‑term damage the dumping of waste into a river can cause. Cultural habits are also to blame: offerings, which have been traditionally thrown into the river, have been considered a custom despite damaging the ecosystem. Bad waste management makes matters worse, because after large gatherings the governments have found it hard to put up bins, collection systems, or cleaning personnel. Crowded sites during rituals make it harder to manage waste disposal, and enforcement of rules on pollution doesn’t really work, and existing laws against polluting the river hardly ever get enforced.

For regular citizens, the situation is disappointing. On the one hand, the Ganga is revered as a kind of mother, as a source of spiritual power. On the other, it is used cavalierly, where trash and sewage wash readily into its waters. This contradiction is often reflected in social media posts, which decry the hypocrisy of worship followed by pollution. The sentiment was perfectly captured by the statement “We worship Ganga at night and pollute it in the morning.” It mirrors the anger and disappointment of people who are eager to see real change and not symbolic rituals.

There is cause for concern, but there are feasible measures that could move us closer to a resolution. Awareness programmes can inform congregants regarding the consequences of pollution and facilitate responsible actions. Eco-friendly rituals such as making offerings with biodegradable materials for offerings, and discouraging the use of plastic, can prevent waste. Authorities must set up bins, collection centers, and cleaning personnel to take place in the vicinity after ceremonies so the objects can be properly put down on the way back and cleaned up. Community participation can also play a role, with local groups and volunteers helping to monitor and clean riverbanks. Strict enforcement of regulations (such as fines and penalties for polluting the river) can also deter pollution. Waste filters in important areas and barriers along the river's edge are ways to keep rubbish out of the river.

The Ganga is not only a river; it is a lifeline to millions of people, providing water for drinking, farming, and daily use. Polluting it is disrespectful not just to faith but to health and the environment. They must be responsible; leaders, temple authorities, and citizens. So true devotion should be to the river (what it is), not to destroying it.

Worshipping the Ganga but polluting it indicates a discrepancy between practice and faith: If the river is sacred, the two should be treated with reverence in prayer and action. Appreciation through rituals is meaningful, but it should be supported through concern for the environment. And when this gap is not filled, the Ganga will be a signifier of devotion on the outside, but a victim of neglect on the inside.